Introduction

Feminism is not a new concept. Women have defended their rights, as they perceived them, on various battlefields throughout history. Even so, in the modern sense, Feminism can be said to have begun around 1830's with the women's movement for suffrage. Women, as a collective unit, stood together asserting their rights as members of society to take equal part in the government that supposedly represented them. They finally won that right in 1920. This movement is now known as the First wave of Feminism. Some forty years later women began mobilizing again. This Second Wave of Feminism rose out of the demand of equal pay for equal work. They demanded the right to a non-discriminatory work place, in which sexual harassment would be legally punishable. They also fought for the right to abort unwanted fetuses. The right to determine whether or not to have children. These issues, in particular, galvanized the women taking part in the Civil Rights movement. They won the fight (at least to some degree). This fact has helped to give rise to a Third wave of Feminists with diverse ideas of what Feminism means, where the women's movement should be heading, and how to get there (Baker and Kline, 1996). My research was prompted by a theory that Third wave Feminists were heavily influenced by a generational effect. The idea was that women of Generation X (cohort group with birthdates 1961- 1980) were not represented by the ideas of the Second Wave, and that they were essentially striking out against the idea of Feminism (Holtz, 1995). My theory was disproved by the research. It this is true for a large part, but the link is not through a generational effect. Women are attacking traditional ideas of Feminism, but the causal events are much more varied. One of the predominant indicators, it seems, of feminist identity is the issue of motherhood.

Background

The concept of motherhood and child rearing was one of the central debates of women's Civil Rights movement. Women such as Shulmaith Firestone in The Dialectic of Sex, "called for artificial wombs to free women from the restrictions of childbearing (Baker and Kline, p. XV)." Germaine Greer's solution was to found "a huge baby farm in Italy where children would be raised by a 'local family' and could occasionally be visited by mothers and fathers (Holtz, p. 21)."

These were women who wanted to bring about a drastic change in the way American society rejected men and all symbols of patriarchy completely. They would remain single and childless, refusing the shackles of the family unit (Baker and Kline).

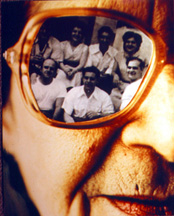

The movement was not, however, burgeoning only from young, single, non-mothers, but was also joined by women in families. These women were fighting the inequity they saw in society and often in their own households. Many already had children but were fighting the societal obligation to have them. Many of them joined the movement to create a world in which their daughters could grow up without the restrictions they, as women, had faced. These women were often forced to fight a two-front war. On one side was the status quo system of patriarchy that sought to use their position as mothers to enslave them. On the other was the hostility of more radical Feminists claiming them to be traitors for allowing themselves to be enslaved to the "mommy track." They fought this war and along with all the others helped establish a more equitable environment for children whether seen as a joy or a necessary evil. The daughters of these Feminists grew up, often fully aware of their mother's activities. For many, involving their mothers was essential to what they were doing. They were raised to question patriarchy and dogma. They were taught to challenge the status quo. They have grown up in a world, which their mothers fought for them to have one in which they are protected, legally at least, from sexual harassment. One in which they can expect to be anything they want to be. The big battles have been won. This has led to the diversification of interests in the movement. Third Wavers, no longer needing solidarity on issues such as equal opportunity, can feel free to argue and splinter on issues like abortion. They can choose not to get married or choose to have a large family. This lack of unity and proper obeisance to the strictures of their foremothers in the movement has led to a greater splintering among Feminists and that is a generational splintering.

Identity Formation

Family can be cited for its formation of feminist identity as the primary socialization group. Women of the second and Third wave have formed a large part of their identity around the issue of parenthood and childhood. There are three predominant group identities examined in this study. The First is that of the Second Wave radicals who attack the institution of motherhood as a form of slavery and subjugation of women. The second is that of Second Wave mothers and sympathizers that seek to modify the role of women within familial institutions and enact change from the inside out. Finally, there are the Third wave women, who, though extremely diverse on social issues, are linked by their structural position of acting from a position of a greater, even assumed, equality to men. These three groups have been a primary cause of identity formation for one another, and it is through their interactions with and reactions to one another that the feminist movement grows and changes.

Second Wave Radicals

The radical Second Wave Feminists, as described, have rejected the patriarchy completely including institutions of motherhood. They have formed their identity around the belief that childbearing is used by the patriarchy to enslave women. In American society, "Mothers are the ideal, preferred caretakers of children (Gross, 1998, p. 270)." This is expensive for women not only monetarily but also, and more importantly, temporally. Women become mothers. This becomes their identity. They become burdened with guilt when leaving their children in the care of others, and the adequacy of their ability to mother becomes a daily concern. This sort of enslavement to a child is absolutely rejected by radical Second Wave Feminists. They find it essential to be independent and free from restraints. They need to be free to pursue their own interests and desires and this is impossible within the confines of motherhood.

The sentiment of these Feminists is summed up in 1979's Kramer vs. Kramer when Meryl Streep approaches her abandoned son saying, "I have gone away because I must find something interesting to do for myself in the world. Everybody has to and so do I. Being your mommy is one thing but there are other things (Holtz, p. 21). "

The Second Wave radicals have shaped their identity around being a feminist. They are often militant and judgmental of women that choose a lifestyle of what they see as subjugation. The Second Wave radicals reject their Second Wave sisters as either weak and complacent, or trapped and overwhelmed. They resent Third wave Feminists for their fractionary actions, and accuse them of having "'forgotten the multifaceted political struggles of [their] Second Wave foremothers and [are] swayed to ingratitude by a stilted vision of the Second Wave as a privileged, homogenized movement typified by the National Organization for Women (Detloff, 1997, p. 78)." In one account, a Second Wave panelist was asked by a woman in the audience "What should young women say to their feminist foremothers?" The response was "Thank You! (Clark, 1997)"

Second Wave Mothers

Mothers joined the feminist movement in droves, eager to claim a place for their children. They had families and were happy with them. They felt social institutions needed to be reformed not decimated. Their identity in a sense was formed by who they were as wives and mothers. Many found Feminism as the crucial voice that helped them balance what they wanted as a woman, and what they needed as a person. One woman, Alix Kates Shulman, states, "Feminism reversed the submission and compromise that were part of the surrender of marriage. I could carry my children with me into the future we were creating (Baker and Kline, p. 89)." The friction between the Radicals and the Mothers was great even during the Civil Rights movement, but at that time the two groups looked beyond one another's "transgressions" for the good of all women. The Second Wave Mothers were the moderates of the women's movement. They, all along, sought equality and balance between the gender roles.

The Second Wave mothers were the first to really split on a major issue from the movement. They rejected the idea that marriage and family had to lead to subservience. While they rejected their cohort's extremism, they had not gone so far as to reject the movement. The hard-line attitude of the radicals is looked at, by most mothers, as simply not for them but effective in instituting change. The Second Wave mothers have reveled in the growth of equality in the United States and the fact that young women today can take for granted all the work they did. They see this "disrespect" as a sign of their success and a reward for work well done. For their daughters to grow up assuming that they are equal to men and that they deserve to have all the same rights and privileges of men reaffirms their choice to be a mother and a feminist. It validates who they are (Baker and Kline).

Third Wave Women

Equal pay for equal work. A work environment free of sexual harassment. The right to pursue any career. These assumptions are the gift bestowed upon Third Wave women by their feminist foremothers. However, the gifting has had consequences. With society now, for the most part, accepting the idea that women are equal to men, women have had time to look at their differences. Some take as their task to actualize the phrase "equal pay for equal work" citing that "Women still earn an average of only 71 cents on the dollar earned by men, according to the Labor Department's Women's Bureau (Clark, 1997, p. 175)."

Others have focussed on rights to an abortion and preventing recent attempts to overturn Roe v. Wade. Still others have fought to get better health care and neo-natal care for unmarried women with no insurance. The divisions have lessened the impact of the whole but have in a way shown the maturity level to which the movement has grown. Third Wave women no longer need to identify themselves as feminist. Third Wave identity has been shaped by their foremothers to allow this. It is no longer a revolutionary act to speak ones mind. It is no longer defiant or occupational suicide to reject a superior's unwanted advances. Third Wavers have been taught to question and think for themselves, at least to some extent. Some, however, claim that their feminist foremothers do not allow them to speak for themselves. For instance, one group, the Generation GAP, was formed as a result of a 1995 National Women's Studies Association conference in which "younger women at the conference felt misrepresented, spoken for and spoken at but not heard (Detloff, p. 77)."

Many Third Wave women, such as, Elizabeth Fox-Genovese feel that the Second Wave movement places too much importance on the women's movement. As Fox-Genovese states in her book Feminism is NOT the Story of my Life "even when the women whom I interviewed and with whom I had been speaking with informally knew little or nothing about feminist positions, they had a gut sense that Feminism was not talking about their lives (Fox-Genovese, 1996, p. 2)." Kellyanne Fitzpatrick pushes this sentiment even further questioning whether, in the modern economic environment, "A twentysomething female college graduate wondering why she pays for entitlements she'll never receive may have more in common with men her own age than with older women who rely upon these entitlements (Clark, p. 178)."

Conclusion

It is nothing new to say that identities are shaped by our experiences and interactions with people close to us, but feminist identity seems to be strongly shaped around one issue: motherhood. For radicals, it was the rejection of enslavement to a child that shaped their identity. For Second Wave mothers, it was the hope and drive to make the world a more equitable place for their daughters. Third Wave women have formed their identity in an environment, in which, equality is assumed and their "mothers" are no longer addressing issues that are relevant to them. Sheila Tobias, a Feminist author, cites this growth from near-unanimity in the First Wave to slight differences in the Second Wave to a new, complete, dispersal of cohesion as the death of the movement. She fears that Feminists are in danger of remarginalizing themselves when they have gotten so close to their goal of complete equality (Ackelsberg, 1998, p. 725).

The solution seems to me to lie in the formation of a Fourth Wave that would re-unify women and celebrate the ideal of diversity and freedom of thought. This time the celebration would not be of freedom from men but freedom from themselves. In re-unifying and accepting their differences they might be able to continue the forward progress and halt not only the male backlash that Susan Faludi postulated, in her manifesto Backlash, but also the backlash of women that feel ostracized because they have different views and feel underrepresented in the movement.

--Jeremiah Stevens

Bibliography

Ackelsberg, Martha A. "Faces of Feminism: An Activist's Reflections on the Women's Movement" review. The American Political Science Review, 92, 3, 719-720.

Baker, C. L., & Kline, C. B. (1996). The Conversation Begins: Mothers and Daughters Talk About Living Feminism. New York: Bantam Books.

Clark, Charles S. "Feminism's Future." The CQ Researcher- Washington, 7, 8, 171-178+.

Detloff, Madelyn. (1997). Mean Spirits: The Politics of Contempt Between Feminist Generations. Hypatia- A Journal of Feminist Philosophy, 12, 92-99.

Fox-Genovese, Elizabeth. (1996). Feminism is NOT the Story of My Life: How Today's Feminist Elite has Lost Touch With the Real Concerns of Women. New York: Bantam Books.

Gross, Emma. "Motherhood in Feminist Theory". Affilia, 13, 3, 269-272.

Holtz, Geoffery T. (1995).Welcome to the Jungle: The Why Behind Generation X. New York. St. Martin's Griffin./p>

Siegel, Deborah. (1997). "The Legacy of the Personal: Generating Theory in Feminism's Third Wave." Hypatia- A Journal of Feminist Philosophy, 12, 69-75.